Tall Fescue and Mycotoxicity

Tall Fescue first appeared as a forage choice in the United States during the early 1940s. Widely planted, it was easy to establish, tolerant, and tough. It could adjust to heavy grazing and climatic changes, the grass eventually covered some 35 million acres throughout the United States. As more and more animals began to graze on the hearty pasture, health problems were reported. Cattle fed fescue appeared unthrifty and their milk production dropped. Horse breeders began having foaling problems with mares that were fed the grass. Mares fed fescue grass or hay might show a tendency to abort, prolonged gestation (and related dystocia), thickened and or retained placenta, and agalactia (absent to decreased milk production).

The story of tall fescue, in particular the variety known as Kentucky-31 is truly remarkable. In 1931, Dr E.N. Fergus, University of Kentucky, visited the W.M Suiter Farm in Menifee County, Kentucky. While he was on the Suiter Farm, Dr Fergus observed a tall fescue ecotype growing on a mountainside pasture. Being impressed with what he saw, Fergus collected seed from the patch. The collected seed was distributed and tested at several locations in Kentucky. The results from these test plots were promising and this led to the release of Kentucky-31 in 1943.

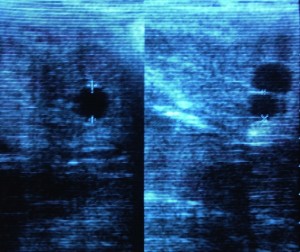

Charles Bacon, a plant pathologist at the Richard Russell Research Center in Athens, Georgia, discovered a fungal endophyte, Acremonium coenophialum (later renamed Neotyphodium coenophialum) living within tall fescue grasses. Not visible to the naked eye, the fungus is transmitted only through the seeds. J.L. Monroe et al. (1988) demonstrated the deleterious effects of allowing broodmares to graze infected tall fescue. They proved that Acremonium produces the toxin that causes fescue mycotoxicity. Twenty-two mares were divided into two groups. One group grazed endophyte infected pasture from the end of their first trimester of pregnancy through parturition. The other group of mares was maintained on endophyte-free fescue. No clinical problems were experienced by those mares kept on non-infected fescue. The group on the infected fescue experienced significant problems. Ten out of eleven mares had dystocia and prolonged gestation. Udder development and milk production were also reduced in these mares. Tall fescue with the endophyte was found to contain ergot alkaloids, most notably ergovaline. Ergovaline is hypothesized to be the toxic principal; ergovaline acts as a dopamine agonist in the pars distalis of the hindbrain, suppressing prolactin secretion and leading to clinical expression of toxicity.

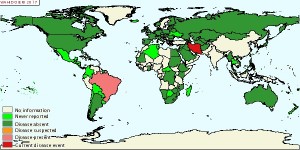

Clearly, infected tall fescue should be used cautiously as a pasture grass. Unfortunately, tall fescue is the predominant forage grass in much of the southern and southeastern the United States. Of the over 35 million acres grown, it is estimated that 60% contains the endophyte. This percentage is even higher east of the Mississippi River, where over 70% of pastures are contaminated. Fescue itself is an excellent forage. As mentioned above, it is hearty and a good forage yielder. The endophyte itself doesn't cause problems for all horses, just pregnant mares in their last third of gestation. Endophyte-free fescue pastures are expensive to establish, and the endophyte-free varieties have not grown as well or been as hearty as the tall fescue (K-31) cultivar.

December 2001

Citations

Bacon CW, Porter JK, Robbins JD, and Luttrell ES: Epichloe typhina from toxic tall fescue grasses. Appl Environ Microbiol : 34(5):576-581, 1977.

Monroe JL, Cross DL, Hudson LW, Henricks DM, Kennedy SW, and Bridges WC: Effect of selenium and endophyte-contaminated fescue on performance and reproduction in mares. J Equine Vet Sci : 8:148-151, 1988.

Dr. William B. Ley DVM, MS, DACT Articles

Related Links

Allowed: 64M/67108864KB.

Current: 8495KB. Peak: 8565KB.